2018 is drawing to a close. Barring a quick piece on The Tree of Life, I have been utterly useless for writing about art this year, but I’ve still taken in a lot of it, and I wanted to leave a record of the best bits here. Here’s to a more productive 2019!

Movies

Phantom Thread (dir. Paul Thomas Anderson)

So. This is my favorite movie of all time.

Barry Jenkins put it this way: “PHANTOM THREAD is just exquisite, an unfiltered work; a sublime object. Object in the sense that, when viewed from different angles, in varying moods, it reveals more and more of itself, other emotions and, for a film overrun with aesthetic objects, deepened ideas.” This movie is many things. It’s a horror story, a romantic comedy, a psychological thriller, a Gothic melodrama, a love letter. It’s delightful, chilling, unbearably sad. It’s Vertigo by way of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, or Punch-Drunk Love by way of Gone Girl.

Jonny Greenwood’s score is on a whole other level from anything he’s done before—sinister, aching, operatic. The film grain’s diffusion of the image renders everything as though it were shot through lace. Daniel Day-Lewis and Vicky Krieps go for each other’s throats with their acting, the former as excellent as ever and the latter a revelation.

I’ve thought about this film every single day since I first saw it in January this year. I suppose you could say it’s haunted me. But, as Reynolds Woodcock would say, “It’s comforting to think the dead are watching over the living. I don’t find that spooky at all.”

Possession (dir. Andrzej Żuławski)

Physically exhausting to sit through. Probably the most singularly nasty movie I’ve ever seen—nearly two solid hours of Sam Neill and Isabelle Adjani’s estranged couple ripping each other apart bodily and emotionally. The disintegration of their marriage is so upsetting that I was worried that the appearance of the Lovecraftian, tentacled horror that Adjani is sleeping with would deflate the tension with silliness—instead, it simply ratchets up the film’s perverse aura. It feels cursed, as though we’re watching something genuinely unholy.

The Favourite (dir. Yorgos Lanthimos)

Blackly hilarious, deliciously mean-spirited, and ultimately heartbreaking. Olivia Colman, Emma Stone, and Rachel Weisz give their all to hurting each other in increasingly vicious ways, and the script’s off-kilter, acid humor is grounded by the absolutely breathtaking production design, costuming, and cinematography; the latter especially, full of rich blacks, candlelit compositions, and frequent camera movement, is stunning on a theater screen. Lanthimos’ best film to date, and hopefully the one that finally gets him some Oscar gold.

The Man with No Name Trilogy (dir. Sergio Leone)

Filled in one of my biggest cinematic blind spots this year courtesy of Trylon Cinema’s triple screening. A Fistful of Dollars is rough in all senses of the word—its raw quality can be effective, but it doesn’t fully succeed in escaping the constraints of its almost nonexistent budget. For a Few Dollars More and The Good, the Bad & the Ugly, though, are absolutely perfect. The highest highs of the trilogy come during the latter—the final cemetery confrontation is almost otherworldly in its flawlessness—but for my money For a Few Dollars More is the overall best of the lot, perfectly balancing the lean, campy feel of its predecessor and the operatic ambitions of TGTBATU.

Miller’s Crossing (dir. Joel and Ethan Coen)

Wrapped up my journey through the Coens’ filmography with one of their best, among the most perfect cinematic magic tricks I’ve ever seen. Borrowing liberally from Dashiel Hammett and Yojimbo, it’s not a gangster movie so much as a devilishly clever con-artist flick where everyone happens to be wearing trenchcoats. Gabriel Byrne’s Tom joins Llewyn Davis and Mattie Ross as one of the brothers’ finest protagonists.

Bringing Out the Dead (dir. Martin Scorsese)

For the most part, I have the same problem with Scorsese that I have with Guillermo del Toro—I admire his films without having a shred of feeling for them. Taxi Driver, Goodfellas, The Wolf of Wall Street—all are wonderfully crafted movies that I care nothing about. Bringing Out the Dead is the exception, a hellish fever dream of death and sickness and the toll that empathy can take on the human psyche. Nicolas Cage is magnificent, his performance full of bone-deep weariness and punctuated by bouts of manic despair.

The Passion of Joan of Arc (dir. Carl Theodor Dreyer)

Watched with Richard Einhorn’s Voices of Light as accompaniment. Even to an unbeliever, it felt like a truly holy experience—I can’t add anything that hasn’t already been said, but Renee Falconetti’s facial expressions are constantly on the verge of bursting out from Dreyer’s constricted frames, the divinely inspired struggling against the confines of the mundane.

The Other Side of the Wind (dir. Orson Welles)

This would have melted people’s brains if it had been released during Welles’ lifetime. The crazy bastard invented the found footage genre twenty years before the rest of the world caught on, and slapped his edits together in a style that’s best described as F for Fake on speed. All the performers are wonderful, and John Huston is a titan of self-loathing and disgust, but it’s ultimately Peter Bogdanovich who walks away with the picture—the parallels to his real-life relationship with Welles here are kind of devastating. (“What did I do wrong, Daddy?”)

One could argue that it’s not a “true” Welles feature—60% of the editing was done by others, and bits and pieces of dialogue had to be looped forty years later (Bogdanovich’s casual mention of cell phone cameras in the opening narration is jarring)—but Welles’ entire body of work is made up of films that were slashed to pieces by producers or shot in bits across years and countries. By its very incompleteness, The Other Side of the Wind is the perfect capstone to his career. It’s a miracle that we have it, and god bless Bogdanovich and the rest for seeing it through.

Television

Better Call Saul: Season Four (created by Vince Gilligan and Peter Gould)

It’s not over yet (fifth and hopefully final season is on the way), but I’m comfortable in saying that Better Call Saul is a better show than Breaking Bad. Bob Odenkirk hits all-timer levels of good this season; watching the formerly decent Jimmy McGill fully twist himself into an embittered, scumbag Saul Goodman is heartbreaking in a way that Walter White embracing his inner monster never was. There are points where the show embraces its nature as a Breaking Bad prequel too much—all the stuff involving Gus Fring’s drug lab is essentially a different show at this point, and I struggle to see how its thread will intertwine with Saul’s before the end—but it’s still the best thing currently on television.

Books

Blindsight – Peter Watts

Consciousness is a glitch in evolution. Your self is a parasite. Don’t think the rest of the universe doesn’t see it as such. (Absolutely chilling in its implications, and the narrative it’s couched in—Alien as aborted first contact mission—is among the most stylistically sound hard SF ever written. Go in having read Thomas Ligotti’s diatribe of pessimist philosophy The Conspiracy Against the Human Race.)

Sometimes a Great Notion – Ken Kesey

A sprawling American epic that I absolutely hated for the first 100 pages and wound up falling completely in love with. Its admiration for rugged masculine individualism is largely bullshit—and the socialist in me is reluctant to admit they like a book about the heroics of a strikebreaker this much—but Kesey’s ecstatic prose and flair for the melodramatic overcame all my doubts by the end.

The Cipher – Kathe Koja

Reads like a period piece now—from the supremely assholish cast to the videotape MacGuffin, it practically screams 90s—but the central conceit, a perfectly black hole with no bottom that suddenly forms in the main characters’ apartment building, remains primally spooky. It’s a concept that on its face would seem ideally suited to a short story, but Koja manages to spin her tale for almost 400 pages without compromising any of the constantly building dread.

War Crimes for the Home – Liz Jensen

Memory at war with itself, tight-lipped English humor deployed as a weapon against the void of the past. Reminded me constantly of Kazuo Ishiguro, but where his books are perfect jewels of sadness, Jensen relieves pressure with a constant flow of humor, allowing for an experience that’s less oppressive but devastating all the same.

Against Memoir: Complaints, Confessions & Criticisms – Michelle Tea

Whether the topic is art criticism, intersectional feminism, sexuality, or (contra the title) her own past, Michelle Tea consistently brings a discerning eye and a deft pen. Forms a companion of sorts to her novel Black Wave, taking all the tangled-up thematic threads of its preapocalyptic California and separating them to stand alone.

The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism – Edward E. Baptist / Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II – Douglas A. Blackmon

Reading these back-to-back was soul-crushing but necessary. Slavery by Another Name is the more emotionally engaging read—both because the horrors it exposes are less well-known than antebellum slavery and because its momentum is kept up by the courtroom-drama narrative it weaves into its listing of atrocities—but it hits far harder following upon The Half Has Never Been Told, whose dispassion in accounting the millions of black bodies that America’s fortune was built upon is the stuff of nightmares.

The Third Reich Trilogy – Richard J. Evans

Exhaustive in all senses of the word—coming in at almost 3,000 pages, this is a dense but eminently readable history of Nazi Germany from the horrors of the post-WWI economic collapse all the way through the Allied victory. The thing that stuck with me the most after reading was just how wrongheaded the myth of the Nazis as an ultra-efficient regime of terror is. The litany of bungled propaganda campaigns, redundant government offices, and self-sabotage that composes much of The Third Reich in Power would be comical if we weren’t aware how the story ended; that the Nazis got as far as they did was due to luck in the face of incompetence, not any sort of superior planning. It’s a sobering reminder that evil doesn’t have to be smart or even particularly skilled in order to succeed.

You Never Give Me Your Money: The Beatles After the Breakup – Peter Doggett

A grueling account of the Fab Four’s breakup and its aftermath, one in which everyone comes off as an asshole and no chance at reconciliation is left unsquandered. And yet, the magic of the Beatles is that their music is more than the men who composed it—right after I finished this book, I sat down, listened to all of Abbey Road, and was as enchanted as ever. That’s the most miraculous thing about the band—in the midst of what at times came very close to all-out war amongst each other and their legal teams, they were still able to pull it together and give us the best send-off in pop music’s history. (No, Let It Be doesn’t bloody count.)

Music

Dirty Computer – Janelle Monáe

Absolute masterpiece, a blast of pure joy that perfectly melds the personal and the political. Monáe’s previous tendency toward sci-fi sprawl is given focus by the urgency of her coming out—this is an extremely tight record, and every single song is a raised middle finger toward those who would try to keep the marginalized quiet. Nor does its focus on social justice mean that it’s a dour time—from the gleefully in-your-face double entendres of “Screwed” to the Prince-penned synth groove of “Make Me Feel,” Monáe revels in her newly open queerness.

Mingus Mingus Mingus Mingus Mingus – Charles Mingus

Mingus once infamously punched his trombonist in the mouth, causing him to lose a full octave on the instrument. If you were searching for the sonic equivalent to that punch, Mingus x 5 is it. Not his most important record—Mingus Ah Um and The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady are the pillars there—but I fell in love with the absolute ferocity he and his band bring to this re-recorded selection of his “greatest hits.” It’s encapsulated by the sudden explosion into violence that hits a little after two minutes into “II B.S.,” Walter Perkins hammering so hard on his drums that it sounds as though he’s about to punch right through them—the song seems genuinely dangerous, as though it’s on the verge of breaking out of your speakers and coming for you.

The Goat Rodeo Sessions – Yo-Yo Ma, Stuart Duncan, Edgar Meyer & Chris Thile

Four instrumentalists working at the absolute top of their game—Chris Thile and Yo-Yo Ma are literal wizards on the mandolin and cello, respectively, but Meyer’s bass and Duncan’s fiddle are more than up to the challenge. The latter’s run at 1:22 of “Attaboy” is what flying must feel like.

Castor, the Twin – Dessa

Could have been a phoned-in gimmick record—it’s almost entirely re-recordings of old songs with live instrumentation—but instead it’s Dessa’s best album. The organic, smoky quality of the production suits her somewhat quavery voice, and the selection of material is excellent—errs on the side of singing rather than rapping, but balances the lyrics evenly between fiery independence and mournful loneliness.

Life on Earth – Tiny Vipers

A lone, keening voice mumbles and sighs over a spare acoustic guitar, elliptical songs blending into each other in a single apocalyptic dirge. There are moments of warmth amid the gloom, but by the time the album comes to a close there is nothing but regret and fear. A haunting triumph of minimalism.

2 Nice Girls – Two Nice Girls

The transition from “I Spent My Last $10.00 (On Birth Control and Beer),” a tongue-in-cheek honky-tonk lament for lost lesbianism, to “Sweet Jane (With Affection),” an entirely genuine, truly ethereal Velvet Underground cover, is my favorite moment of anything this year.

Video Games

Horizon Zero Dawn – Guerrilla Games

Like any prestige AAA title, this is frequently held up as a masterpiece when it’s anything but. The story is typical tired hero’s journey stuff, and the optics of the very white heroine’s culture being almost wholesale ripped off from Native American culture are cringey at best. That said, God I fell in love with this game. In addition to the sheer stunning beauty of the visuals, the art direction on the robo-dinosaurs is impeccable and full of life, and the fluid combat is a dream. I generally dislike open-world games—I need narrative momentum and linearity too much to enjoy side quests—but I spent fifty hours on this one just bathing in the world.

Doom – id Software

Sometimes you’ve just gotta blow apart literally everything with a shotgun.

Tetris Effect – Monstars Inc. & Resonair

The fusion of music and visuals with the classic Tetris setup is truly enthralling—I’d spend what felt like a little while trying to clear a level only to look at the clock and see that two hours had passed. The more difficult stages are occasionally nightmares to complete, but the overall experience never stops feeling therapeutic.

Honorable Mentions

Movies

- His Girl Friday (dir. Howard Hawks)

- M (dir. Fritz Lang)

- Network (dir. Sidney Lumet)

- Shoplifters (dir. Hirokazu Koreeda)

- Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (dir. Mike Nichols)

- Blindspotting (dir. Carlos Lopez Estrada)

- Kiki’s Delivery Service (dir. Hayao Miyazaki)

- Mission: Impossible—Fallout (dir. Christopher McQuarrie)

- Wake in Fright (dir. Ted Kotcheff)

- George Washington (dir. David Gordon Green)

- First Reformed (dir. Paul Schraeder)

- The Death of Stalin (dir. Armando Iannucci)

- Wild at Heart (dir. David Lynch)

- Deep Cover (dir. Bill Duke)

- The Ballad of Buster Scruggs (dir. Joel and Ethan Coen)

- Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse (dir. Bob Perischetti, Peter Ramsey, Rodney Rothman)

- The Miseducation of Cameron Post (dir. Desiree Akhavan)

- Naked (dir. Mike Leigh)

- Hereditary (dir. Ari Aster)

- Columbus (dir. Kogonada)

- My Own Private Idaho (dir. Gus Van Sant)

Books

- Home, Marilynne Robinson

- The Intuitionist, Colson Whitehead

- The Will to Battle (Terra Ignota #3), Ada Palmer

- Operation Paperclip: The Secret Intelligence Program That Brought Nazi Scientists to America, Annie Jacobsen

- Middle Passage, Charles Johnson

- An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States, Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz

- Listen, Liberal; Or, What Ever Happened to the Party of the People, Thomas Frank

- Without a Net: The Female Experience of Growing Up Working Class, Michelle Tea (ed.)

- Not That Bad: Dispatches from Rape Culture, Roxane Gay (ed.)

- Nobody Knows My Name, James Baldwin

- The Recovering: Intoxication and Its Aftermath, Leslie Jamison

- The Pillowman, Martin McDonagh

- The End of Policing, Alex S. Vitale

- The Art of Cruelty: A Reckoning, Maggie Nelson

- Whipping Girl: A Transsexual Woman on Sexism and the Scapegoating of Femininity, Julia Serano

- Paul Takes the Form of a Mortal Girl, Andrea Lawlor

- An Unkindness of Ghosts, Rivers Solomon

- The Freeze-Frame Revolution, Peter Watts

- Gerald’s Game, Stephen King

- The Monster Baru Cormorant (The Masquerade #2), Seth Dickinson

- Terrence Malick: Rehearsing the Unexpected, Carlo Hintermann and Danielle Villa (ed.)

- Devotions, Mary Oliver

- The Only Harmless Great Thing, Brooke Bolander

- The Essential Dykes to Watch Out For, Alison Bechdel

- An Artist of the Floating World, Kazuo Ishiguro

- They Came Before Columbus: The African Presence in Ancient America, Ivan Van Sertima

Music

- The Raincoats, The Raincoats

- The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady, Charles Mingus

- Live in San Francisco, Cannonball Adderley Quintet

- Monk’s Dream, Thelonious Monk Quartet

- Chime, Dessa

- Spilt Milk, Jellyfish

- Smokin’ at the Half Note, Wes Montgomery & The Wynton Kelly Trio

- The Great Summit: The Master Tapes, Louis Armstrong & Duke Ellington

- Agharta, Miles Davis

- John Coltrane and Johnny Hartman, John Coltrane & Johnny Hartman

- Charlie Hunter/Carter McLean Featuring Silvana Estrada, Charlie Hunter & Carter McLean & Silvana Estrada

- Chris Thile & Brad Mehldau, Chris Thile & Brad Mehldau

- Shaken by a Low Sound, Crooked Still

- Victory Lap, Propaghandi

- The Virginian, Neko Case & Her Boyfriends

- Bobby Broom Plays for Monk, Bobby Broom

Games

- The Swapper, Facepalm Games

- Mass Effect 3, Bioware

- Bioshock 2, 2K Games

- Prey, Arkane Studios

- Dark Souls, From Software

- Nier Automata, PlatinumGames

In the last 72 hours, I’ve rewatched Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life twice. The first rewatch was my fifth viewing of the theatrical cut. The second was my first viewing of the just-released extended cut, which adds nearly an hour of footage and forms what Malick has called not an expanded film but a new film.

In the last 72 hours, I’ve rewatched Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life twice. The first rewatch was my fifth viewing of the theatrical cut. The second was my first viewing of the just-released extended cut, which adds nearly an hour of footage and forms what Malick has called not an expanded film but a new film.

The Florida Project

The Florida Project Lady Bird

Lady Bird mother!

mother! Dunkirk

Dunkirk 20th Century Women

20th Century Women John Wick Chapter 2

John Wick Chapter 2 The Big Sick

The Big Sick Free Fire

Free Fire Get Out

Get Out Toni Erdmann

Toni Erdmann Good Time

Good Time In This Corner of the World

In This Corner of the World Last Flag Flying

Last Flag Flying

The Meyerowitz Stories (New and Selected)

The Meyerowitz Stories (New and Selected)

Baby Driver

Baby Driver

Silence

Silence

Paterson

Paterson

Star Wars: The Last Jedi

Star Wars: The Last Jedi

Call Me By Your Name

Call Me By Your Name

The Disaster Artist

The Disaster Artist

The Transfiguration

The Transfiguration

A Cure for Wellness

A Cure for Wellness

Logan

Logan

The Shape of Water

The Shape of Water

Icarus

Icarus

A Ghost Story

A Ghost Story

The Beguiled

The Beguiled

Found Footage 3D

Found Footage 3D

Personal Shopper

Personal Shopper

Jim and Andy: The Great Beyond – Featuring a Very Special, Contractually Obligated Appearance by Tony Clifton

Jim and Andy: The Great Beyond – Featuring a Very Special, Contractually Obligated Appearance by Tony Clifton

The Killing of a Sacred Deer

The Killing of a Sacred Deer

Imperial Dreams

Imperial Dreams

Valerian and the City of a Thousand Planets

Valerian and the City of a Thousand Planets

War for the Planet of the Apes

War for the Planet of the Apes

Logan Lucky

Logan Lucky

Coco

Coco

Whose Streets?

Whose Streets?

It

It

Raw

Raw

I Am Not Your Negro

I Am Not Your Negro

Brigsby Bear

Brigsby Bear

Blade Runner 2049

Blade Runner 2049

Molly’s Game

Molly’s Game

Wonder Woman

Wonder Woman

Hidden Figures

Hidden Figures

Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri

Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri

Detroit

Detroit

Atomic Blonde

Atomic Blonde

Mudbound

Mudbound

It Comes at Night

It Comes at Night

Lady Macbeth

Lady Macbeth

I Don’t Feel at Home in This World Anymore

I Don’t Feel at Home in This World Anymore

Manifesto

Manifesto

Murder on the Orient Express

Murder on the Orient Express

Wonderstruck

Wonderstruck

Song to Song

Song to Song

Nocturama

Nocturama

Okja

Okja

All These Sleepless Nights

All These Sleepless Nights

The Void

The Void

Battle of the Sexes

Battle of the Sexes

Darkest Hour

Darkest Hour

The Discovery

The Discovery

Woodshock

Woodshock

Brawl in Cell Block 99

Brawl in Cell Block 99

The Book of Henry

The Book of Henry

The Snowman

The Snowman

Beauty and the Beast

Beauty and the Beast

The Dark Tower

The Dark Tower

Wallace Stegner’s The Big Rock Candy Mountain was my favorite book of the year. A sprawling, semi-autobiographical epic of rum-running in the American Northwest, it’s ambitious and overstuffed and completely absorbing. Where similar family-saga books like Carsten Jensen’s We, the Drowned (another favorite of mine) can end up sacrificing some central narrative in favor of a bird’s-eye view of the multiple generations they cover, Stegner’s novel has as its lynchpin the central figure of Bo Mason, a husband and father whose avarice and frustration constantly battle with his love for his family. His shadow hangs over everyone in the book, and it’s a credit to Stegner’s characterization that he’s a nuanced and heartbreaking figure rather than a simple patriarchal tyrant. I’ll take him over Jay Gatsby as a personification of the American Dream any day.

Wallace Stegner’s The Big Rock Candy Mountain was my favorite book of the year. A sprawling, semi-autobiographical epic of rum-running in the American Northwest, it’s ambitious and overstuffed and completely absorbing. Where similar family-saga books like Carsten Jensen’s We, the Drowned (another favorite of mine) can end up sacrificing some central narrative in favor of a bird’s-eye view of the multiple generations they cover, Stegner’s novel has as its lynchpin the central figure of Bo Mason, a husband and father whose avarice and frustration constantly battle with his love for his family. His shadow hangs over everyone in the book, and it’s a credit to Stegner’s characterization that he’s a nuanced and heartbreaking figure rather than a simple patriarchal tyrant. I’ll take him over Jay Gatsby as a personification of the American Dream any day.

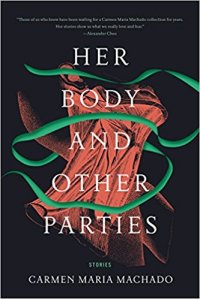

A Fine and Private Place sent me into paroxysms of jealousy. Peter S. Beagle wrote it when he was only nineteen, and it’s as fine a fantasy novel as I’ve ever read, full of affection for and understanding of its characters both dead and living. His We Never Talk About My Brother was also one of a myriad of excellent short fiction collections I read this year, the two best of which were Amelia Gray’s Gutshot and Carmen Maria Machado’s Her Body and Other Parties. The former is a loaded magazine of a book, full of stories that are little capsules of violence and abuse; the latter an elegant, haunting deconstruction of patriarchal power and the male gaze through updates of fantastic and folkloric staples.

A Fine and Private Place sent me into paroxysms of jealousy. Peter S. Beagle wrote it when he was only nineteen, and it’s as fine a fantasy novel as I’ve ever read, full of affection for and understanding of its characters both dead and living. His We Never Talk About My Brother was also one of a myriad of excellent short fiction collections I read this year, the two best of which were Amelia Gray’s Gutshot and Carmen Maria Machado’s Her Body and Other Parties. The former is a loaded magazine of a book, full of stories that are little capsules of violence and abuse; the latter an elegant, haunting deconstruction of patriarchal power and the male gaze through updates of fantastic and folkloric staples. There was all manner of reading that for better or worse resonated stronger than it otherwise would due to the current existential-political hellhole in which we’re currently living. For fiction, Michelle Tea’s Black Wave is reminiscent of Dhalgren in its vision of a city going about its business as the apocalypse looms,

There was all manner of reading that for better or worse resonated stronger than it otherwise would due to the current existential-political hellhole in which we’re currently living. For fiction, Michelle Tea’s Black Wave is reminiscent of Dhalgren in its vision of a city going about its business as the apocalypse looms,  though it jettisons that book’s Joycean complexity for a more elegiac tone; Norman Spinrad’s The Iron Dream, a pulp SF novel-within-a-novel written by none other than Adolf Hitler, is exhaustingly prescient in its deconstruction of toxic tendencies within the fandom that have most recently manifested themselves in Vox Day and his alt-right henchmen. Nearly every single nonfiction book I read touched on our current crisis of civics in some form or fashion; of them, Ta-Nehisi Coates’ We Were Eight Years in Power is the most damning, particularly in its conclusion, which chronicles the rise of Trump as

though it jettisons that book’s Joycean complexity for a more elegiac tone; Norman Spinrad’s The Iron Dream, a pulp SF novel-within-a-novel written by none other than Adolf Hitler, is exhaustingly prescient in its deconstruction of toxic tendencies within the fandom that have most recently manifested themselves in Vox Day and his alt-right henchmen. Nearly every single nonfiction book I read touched on our current crisis of civics in some form or fashion; of them, Ta-Nehisi Coates’ We Were Eight Years in Power is the most damning, particularly in its conclusion, which chronicles the rise of Trump as  Nearly all of my favorite creative nonfiction this year was memoir. The most stylistically straightforward of the lot, Mary Karr’s The Liars’ Club/Cherry/Lit trilogy, was also the best of them, funny and poignant and candid in a way that seems as though she’s just telling you her life story over drinks despite the years of craft and effort that went into the nearly 1,000 pages. Maggie Nelson’s The Red Parts, Bluets, and The Argonauts also form a trilogy of sorts, albeit a much looser one—the first volume is the closest to memoir in the traditional sense, while the latter two

Nearly all of my favorite creative nonfiction this year was memoir. The most stylistically straightforward of the lot, Mary Karr’s The Liars’ Club/Cherry/Lit trilogy, was also the best of them, funny and poignant and candid in a way that seems as though she’s just telling you her life story over drinks despite the years of craft and effort that went into the nearly 1,000 pages. Maggie Nelson’s The Red Parts, Bluets, and The Argonauts also form a trilogy of sorts, albeit a much looser one—the first volume is the closest to memoir in the traditional sense, while the latter two  are syntheses of memoir, essay, prose poetry, and philosophy that touch on grief, love, memory, language, and sense perception in quietly devastating fashion. Roxane Gay’s Hunger, a brutal account of the rape she suffered as a child interwoven with the subsequent cultural and personal abuse she’s suffered as a result of obesity, is heartbreaking, probably the best thing she’s ever written. Outside of memoir, The Empathy Exams is my favorite creative nonfiction title of the year. The titular essay, which uses author Leslie Jamison’s stint as a medical actor to look at how we perceive and respond to pain, is a springboard into a wider study of empathy, trauma, and human interaction. It’s a brilliant collection.

are syntheses of memoir, essay, prose poetry, and philosophy that touch on grief, love, memory, language, and sense perception in quietly devastating fashion. Roxane Gay’s Hunger, a brutal account of the rape she suffered as a child interwoven with the subsequent cultural and personal abuse she’s suffered as a result of obesity, is heartbreaking, probably the best thing she’s ever written. Outside of memoir, The Empathy Exams is my favorite creative nonfiction title of the year. The titular essay, which uses author Leslie Jamison’s stint as a medical actor to look at how we perceive and respond to pain, is a springboard into a wider study of empathy, trauma, and human interaction. It’s a brilliant collection. Adam Kotsko’s The Prince of This World deserves individual mention here as well. A political history of the concepts of Satan and hell, it’s theologically engrossing and morally devastating. Its indictment of the Christian church—specifically the doctrinal shift from identifying Satan with hierarchical power and God with the marginalized and oppressed to viewing minorites as diabolical agents and the powerful as agents of God’s will—is all the more damning in the aftermath of large swathes of evangelicals’ devil’s bargain with Donald Trump and his movement.

Adam Kotsko’s The Prince of This World deserves individual mention here as well. A political history of the concepts of Satan and hell, it’s theologically engrossing and morally devastating. Its indictment of the Christian church—specifically the doctrinal shift from identifying Satan with hierarchical power and God with the marginalized and oppressed to viewing minorites as diabolical agents and the powerful as agents of God’s will—is all the more damning in the aftermath of large swathes of evangelicals’ devil’s bargain with Donald Trump and his movement. Watching the Coen brothers’ rendition of True Grit is akin to watching something Shakespeare might have written, had Shakespeare been born in 19th-century America. There’s always a level of unreality to the dialogue in the Coens’ films, but True Grit is unique in just how bizarre its characters’ speech is. There is perhaps no better example of this than a jibe Rooster Cogburn, the drunken, grizzled U. S. marshal, makes at the expense of the foppish Texas Ranger LaBouef:

Watching the Coen brothers’ rendition of True Grit is akin to watching something Shakespeare might have written, had Shakespeare been born in 19th-century America. There’s always a level of unreality to the dialogue in the Coens’ films, but True Grit is unique in just how bizarre its characters’ speech is. There is perhaps no better example of this than a jibe Rooster Cogburn, the drunken, grizzled U. S. marshal, makes at the expense of the foppish Texas Ranger LaBouef: I’ve been thinking a lot lately about a particular episode of VeggieTales.

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about a particular episode of VeggieTales. There’s a separate grammar to movie musicals than there is to stage musicals—at least, there is to the type of movie musical that Disney makes. Classic stage musicals are pervaded with song. Many of them are almost/entirely sung-through—Les Miserables, Sweeney Todd, The Phantom of the Opera, etc.—and even those that aren’t will have musical numbers peppered liberally throughout their runtime. In this type of musical, songs are the default mode of expression—not every song will be as important as every other, simply because there are so many of them present. They’re not events in and of themselves, though some of them will contain events.

There’s a separate grammar to movie musicals than there is to stage musicals—at least, there is to the type of movie musical that Disney makes. Classic stage musicals are pervaded with song. Many of them are almost/entirely sung-through—Les Miserables, Sweeney Todd, The Phantom of the Opera, etc.—and even those that aren’t will have musical numbers peppered liberally throughout their runtime. In this type of musical, songs are the default mode of expression—not every song will be as important as every other, simply because there are so many of them present. They’re not events in and of themselves, though some of them will contain events.

There are many films that can be considered Lovecraftian horror on a surface level—John Carpenter’s The Thing, what with its preponderance of tentacled limbs and its Antarctic setting, probably chief among them—but if I had to pick which movie best represents Lovecraft’s thematic concerns, artistic trappings, and general aura, it wouldn’t be one of these pseudopod-wriggling entities (admirable as I find many of them). Rather, my choice is a film that, at a superficial glance, doesn’t seem to have much to do with the aesthetic sensibilities of the Cthulhu mythos at all.

There are many films that can be considered Lovecraftian horror on a surface level—John Carpenter’s The Thing, what with its preponderance of tentacled limbs and its Antarctic setting, probably chief among them—but if I had to pick which movie best represents Lovecraft’s thematic concerns, artistic trappings, and general aura, it wouldn’t be one of these pseudopod-wriggling entities (admirable as I find many of them). Rather, my choice is a film that, at a superficial glance, doesn’t seem to have much to do with the aesthetic sensibilities of the Cthulhu mythos at all.